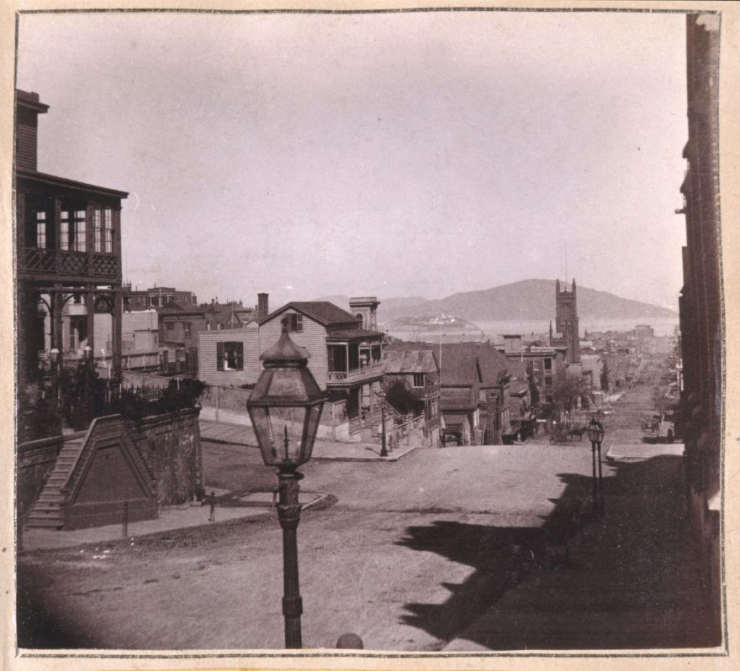

Stockton Street was San Francisco’s first fashionable residential district, when during the California Gold Rush of 1849, and in its wake, many of California’s most-successful pioneers (politicians, lawyers, merchants, etc.) built homes along it, north of Pine Street down toward the North Beach. Some of these notables were W. D. M. Howard, Thomas O. Larkin, Senator William Gwin, and Frederick Macondray. Sitting up at the western edge of the exploding city, Stockton Street then looked down upon the chaos surrounding Portsmouth Square and Yerba Buena Cove; uphill, it was far enough removed to feel somewhat residential, and its heights were best accessed by improved thoroughfares–wood-planked roads–from downtown: Pacific, Washington, and Clay streets. Given these access points, the street quickly grew rather dense.

As the city continued to expand throughout the 1850s and 1860s, the majority of the city’s growth was southward toward Market Street, and along it to the southwest, into St. Ann’s Valley (Union Square area), South of Market, toward Mission Dolores and beyond. This shift southward became discouraging for many of those who had invested early-on in the north part of the North Beach neighborhood, and specifically its waterfront area. While no one doubted Jasper O’Farrell’s (or perhaps George Hyde’s) visions of Market Street becoming the city’s new main artery in the template of William Penn’s Market Street in Philadelphia (though at the time of O’Farrell’s survey in 1847 it was little more than a bunch of sand dunes), there were those that felt the reasons for the stagnation in developing the North Beach waterfront was mostly due to there being no easy route from downtown to that area. For this reason, completed in 1874, Montgomery Avenue (Columbus Avenue today) was cut through the grid from the Financial District to the North Beach, traversing the valley between Russian and Telegraph hills, in hopes of facilitating growth in that direction.

At the same time of the cutting and opening of Montgomery Avenue was the construction of San Francisco’s first cable car line, which ran west up Clay Street from Portsmouth Square to Leavenworth Street (the mechanical barn for this line was located where Le Beau Market is today).[+] At that point, it connected to an omnibus line (think cable car drawn by horses), therefore facilitating development west of Nob Hill: along Van Ness Avenue (which became a sort-of San Francisco Champs-Élysées), Pacific Heights, etc.

With all of this in mind, as the commercial heart of the city was further shifting from Portsmouth Square and Kearny Street to Market westward toward the Union Square area, by the early-20th century, transportation from North Beach to this new commercial heart was only achieved in a circuitous way, in other words, Montgomery Avenue’s initial 1874 mission was now outdated in the 20th century.

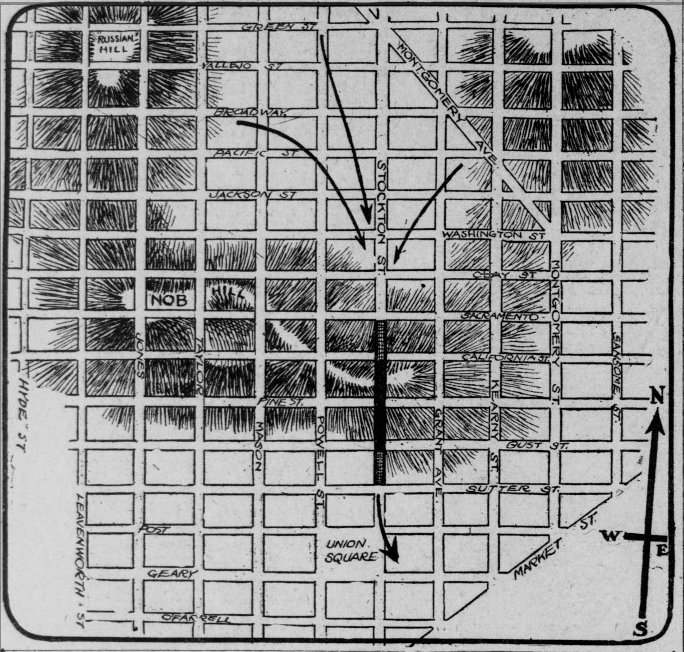

Therefore, in the wake of the earthquake and fires of 1906 which laid waste to the eastern half of the city; with the rebuilding of those districts; eventually, similar to the concerns that brought about Montgomery Avenue–better connecting the North Beach to the commercial district–a number of capitalists resumed talks of tunneling the hills for better transportation solutions, and the first of these tunnels to gain traction was the Stockton Street Tunnel, proposed to city officials in 1909.[1]

At this time, the main spokesman for the proponents of the Stockton Street Tunnel was realtor George Skaller. Other proponents included attorney Curtis Hillyer, engineer A. B. Southard, and capitalist Herbert E. Law.[2] Their initial proposal was to run a streetcar line up Stockton Street from Market, through the new tunnel, all the way to Bay Street. The Downtown Association, during a meeting at the St. Francis Hotel on Union Square, immediately endorsed the proposal: “Nearly every merchant present advocated the granted of this privilege in the belief that it would materially increase business in the newly rebuilt shopping district.”[3]

In June 1909, the bid for the projected tunnel and railway, with extensions going to the waterfront, as well as to the Presidio, was won by Frank D. Stringham and associates, that is, the above mentioned group. Albert J. Lowenberg, president of City and County Bank, was to act as president of the franchise, along with his assistant cashier Joseph L. Goldsmith. Along with George Skaller, and others in the law firm of Hillyer, Stringham & O’Brien, there would also be additional local bankers involved in forming the $1M corporation.[4] However, by September, this assemblage, and their ongoing conversations with the Board of Supervisors became more and more contentious, and therefore the railroad and tunnel started looking doubtful.[5] As Skaller later explained, “When this franchise was applied for, the agitation for municipal ownership was at its height, and the public utility committee of the Board of Supervisors insisted upon inserting provisions in such franchise which were not only objectionable to private capital, but would undermine the very foundation of the investment. The provision that the city could take the road after ten years at its physical valuation, without any compensation for the franchise element, barred all private capital from investing.”[6]

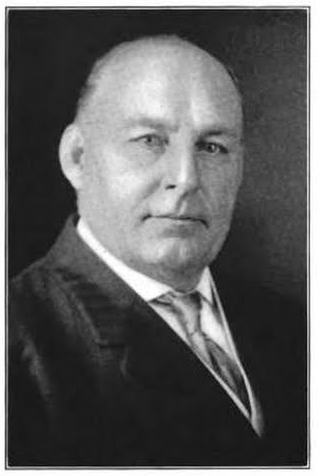

This is when Skaller “immediately gathered . . . all those progressive men who had already recognized [the Stock Tunnel] as one of the city’s greatest necessities.”[7] Therefore entered into the fray, Dr. Hartland Law, brother of Herbert E. Law, one of the original proponents of the tunnel. In the words of Skaller, Dr. Law was “one of San Francisco’s greatest and most civic spirited citizens.” [8] Therefore, with Dr. Law’s assistance, the Nob Hill Tunnel Association was formed for the “purpose of placing into the city’s organic law a statute which would make it possible for the city to undertake and carry out the construction of tunnels.”[9]

Dr. Hartland Law, and his brother Herbert E. Law, were not new to Nob Hill. In fact, just one month before the earthquake and fires of 1906, the Law brothers had come to own the Fairmont Hotel, which was not yet opened.[10] While the hotel was indeed gutted by fire in the 1906 cataclysm, the Law brothers rebuilt its interior, and it opened to the public a year to the date of the earthquake in 1907.[11] Soon after, however, they traded the Fairmont for a tract of land around Fort Mason which they planned to develop, therefore why Herbert was involved as an original proponent of the Stockton Tunnel, and why Hartland now came in to better organize the effort, and make it happen.

Born near Sheffield, England in the 1850s, in 1866 the Law brothers immigrated to Chicago with their parents. In 1884, the brothers came to the Bay Area and established a publishing business with Richard King, known as Law, King & Law. However, their main success came with their founding of the Viavi Company, Inc., which brought their alternative medical practice, the Viavi System of Treatment, to the world.[12] By this time, the Law brothers lived next door to one another in Pacific Heights, at 1910 and 1912 Vallejo St.,[13] and at the time of the earthquake and fires of 1906, when they owned the Fairmont Hotel, Hartland lived at Broadway and Van Ness, and Herbert was on the west side of Russian Hill at 1526 Vallejo St.[14] In the wake of 1906, however, Herbert built a classic townhouse at 1021 California St. atop Nob Hill, today known as “The Jewel Box,” whereas Hartland built a home–also still standing today–in the then-brand-new subdivision of Presidio Terrace.[15] Furthermore, Herbert deepened his ties to Nob Hill in 1926 when he purchased the Chambord Apartments (built in 1921 by James Witt Dougherty) at 1298 Sacramento St.–a building that remains “an architectural curiosity of the first rank in San Francisco”[16]–and added the sixth floor penthouse.

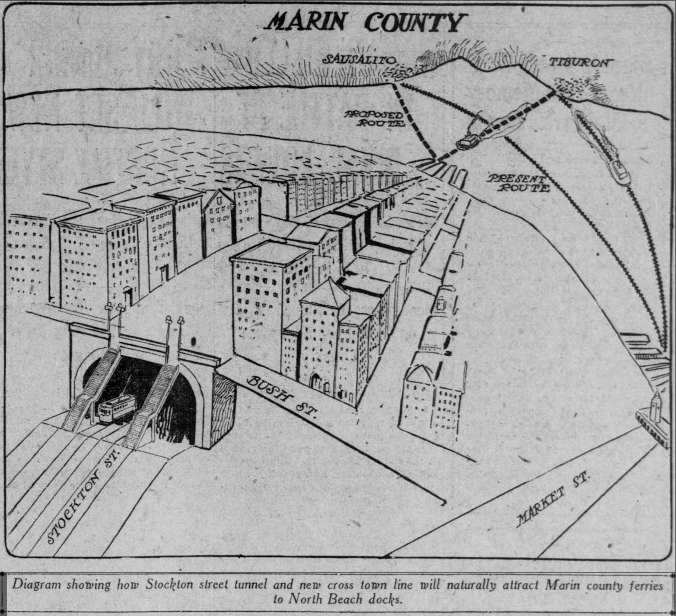

But backing up, in February 1910, with Hartland Law now involved, George Skaller honed in on the benefits of the Stockton Tunnel to the Board of Supervisors: “the improvement would clear the way for the North Shore ferries to make their landings along North beach and relieve the congestion at the [Ferry Building].”[17] Also, at this time, the Nob Hill Tunnel Association re-engaged the Downtown Association.[18] In May 1910, the Call reported, “Headed by Dr. Hartland Law, a committee of the city’s most successful financiers will now set the machinery in motion that is designed to drive the first pick into the south portal of what will soon be known as the Stockton street tunnel.” Law said, “The Stockton street tunnel will solve the greatest traffic problem that has ever confronted the residents and property owners of North beach . . . By opening this underground passage we will bring into immediate touch the businessmen of that district and those of the downtown district. . . . This barrier, which has shut North beach off from the business and social life of the city, will be overcome, and I feel that everybody who understands the situation will enthusiastically support it.”[19]

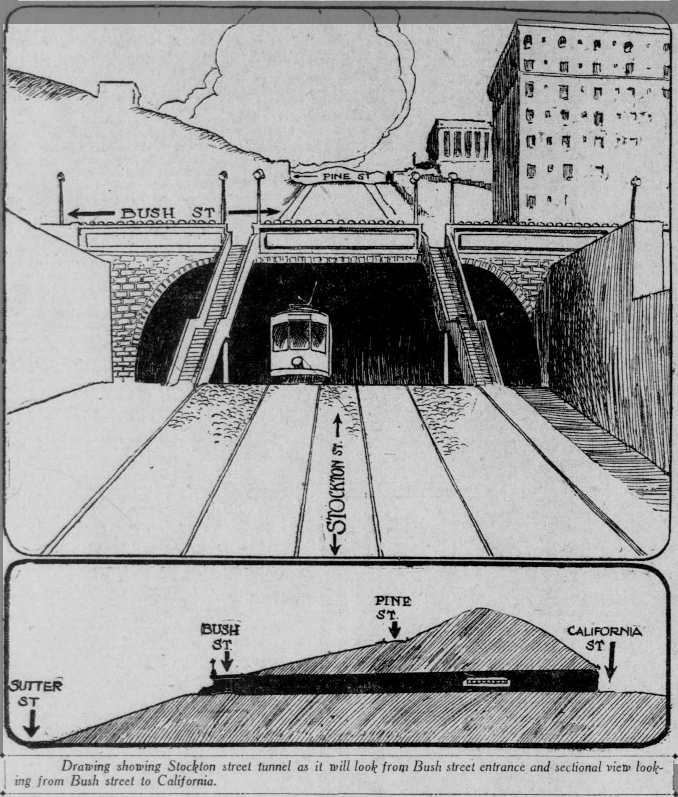

In December 1905, renowned engineer William Barclay Parsons had given a presentation to the Merchants’ Association at the Palace Hotel that laid out a well-thought-out plan for San Francisco’s transit problems. His suggestion was to tunnel the hills, and run streetcars through them. In his presentation, his example was tunneling Nob Hill from the east and west along California Street, starting from the crossing at Grant.

Following the devastation to the city in April 1906, however, in the wake of the earthquake and fires, this was the first time Parsons’s suggestion seemed perhaps doable, and through Nob Hill nonetheless. On May 14, 1910, under the headline “Build the Stockton Street Tunnel Now,” the Call reported, “the Stockton street tunnel may be regarded as a valuable object lesson in demonstration of what may be done by united effort and loyal co-operation without imposing on the property owners any serious burdens.” [20]

In September 1910, NHTA attorney Theodore J. Savage (of Dorn & Dorn & Savage[21]) stated: “That tunnel is going to be built, and before very long the dirt will be flying.”[22] Furthermore, in June, George Skaller–secretary of the NHTA–vocalized more fully the benefits of the tunnel to the city: “Few people realize the possibilities of the North beach section as soon as it is brought into communication with the heart of the city. Perhaps I can best illustrate this by citing the case of the Bronx district of New York city before that northerly section was united with the downtown districts by the subway system. . . . The building of a tunnel through Stockton street and the streetcar lines that will naturally be built through it and down to the water front will naturally cause ferries from Marin county to locate there and there is every probability that docks will be built for ocean steamship lines.

“After the Panama canal is built,” continued Skaller, “steamship companies will land European emigrants here for only $7 more than is charged to Atlantic ports. This will mean that tens and hundreds of thousands of them will be brought here every year. They naturally tend to locate for the time being in the immediate vicinity of where they land. This alone will give an enormous population to the North Beach district. Moreover, the location of the ferries on the North beach shore line will naturally lead to the building of a great number of hotels and lodging houses near the water front to take care of the people who come in from the country. The vicinity of Third and Townsend street station is a good example of this kind of development. It occurs in all cities and towns near railroad stations and ferries. This will have the effect of giving North beach property values similar to those around Third and Townsend . . . The increase of real estate values throughout the whole North beach district will run into the millions.”[23]

By June 1911, however, the project was log-jammed, yet despite that, along with the NHTA, the North Beach Promotion Association (of which Skaller was part of as well), the Downtown Association, and the Merchants’ Association all were requesting work on the tunnel to begin;[24] however, in October 1911, Dr. Benjamin A. Mardis–who owned property at Stockton and Sacramento–sued the city saying his property would be “injured in value.”[25] Interestingly, Mardis’s lawyers in the lawsuit were none other than Hillyer, Stringham & O’Brien, the original proponents of the tunnel! Ultimately, however, though the case went to the California supreme court, the city, and the NHTA prevailed in what in many ways was a landmark decision for future tunneling in the city.[26]

In a letter to the Call, Skaller wrote: “The pioneer in the solution . . . is the Nob Hill Tunnel Association, of which Dr. Hartland Law is president, George Skaller secretary and Theodore J. Savage attorney. In January, 1910, a meeting was held in Doctor Law’s office, attended by a handful of public spirited and determined men, in whose minds the tunnel program was a vital one, and who were resolved to undertake its practical accomplishment. At that meeting the Stockton street tunnel was selected as the most feasible project. . . . By means of this tunnel the immense North Beach district will be brought within easy walking distance of Market street, whereas now it is practically isolated from the downtown district. This district will easily accommodate a population of 50,000 more people than it now has, and this population it will assuredly get, as it will be within such easy distance of the downtown section as to be especially desirable for residence purposes. More than all, it will blaze the way for other projects of equal importance, all of which will contribute immensely to the growth and development of our city.”[27]

In this vein, when the success of “[improvement] club work” and “civic bodies” in the rebuilding the city in the wake of 1906 was reflected upon in 1912, the Call wrote, “The success of [the Nob Hill Tunnel Association] is well known to every one. It brought the matter promptly before the board of supervisors and took legal proceedings to test the validity of the tunnel laws. These were declared defective. No time was lost in passing an amendment to the charter, which remedied these defects. . . . The way is now clear for laying out assessment districts for the construction of all the needed tunnels. . . . Tunnels that bring sections of the city into closer touch with each other constitute one of the city’s greatest needs. Large areas of land in the southern, western and northern sections of the city lie undeveloped because inaccessible. To make these properties more accessible is to greatly increase their value and to build them up as business and residence sections and thereby increase the wealth and population of the city. To the improvement clubs is largely due the credit for whatever good results will flow from tunnel construction.”[28]

In May 1913, work at last started on the Stockton Tunnel,[29] dirt was collected from the boring, carried and dumped into fills at North Beach (therefore in many ways instituting what would later become Fisherman’s Wharf).[30] After a year and a half of work, on Dec. 29, 1914, during a ceremony, the first streetcars passed through the tunnel.[31] San Francisco’s first tunnel was now in operation.

Today, it is interesting to reflect on this as one hundred years after the Stockton Tunnel, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency has been engaged in tunneling underneath Stockton Street, from Market, to a new Muni Metro station at Stockton and Washington streets (Chinatown Station), as part of their Central Subway Project, of which they state: “The Central Subway Project will improve public transportation in San Francisco by extending the Muni Metro T Third Line through SoMa, Union Square and Chinatown. By providing a direct, rapid transit link between downtown and the existing T Third Line route on 3rd Street, the Central Subway will vastly improve transportation to and from some of the city’s busiest, most densely populated areas. . . . By taking transportation underground on busy Stockton and 4th streets, travel times in peak periods will be cut by more than half.”

____========++++++++—-_____—_–_-_-__=+=====++++++_________===++-====++===

[+] Pacific Rural Press, Dec. 27, 1873, p. 409, c. 1; Daily Alta, Oct. 29, 1874, p. 2, c. 2.

[1] S. F. Call, Feb. 18, 1909, p. 1, c. 2.

[2] Ibid., p. 16, c. 2.

[3] Ibid.

[4] S. F. Call, June 29, 1909, p. 3, c. 1.

[5] S. F. Call, Sept. 15, 1909, p. 16, c. 4.

[6] S. F. Call, Aug. 10, 1912, p. 18, c. 1.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] L. A. Herald, March 17, 1906, p. 6, c. 4.

[11] S. F. Call, April 20, 1907, p. 6, c. 1.

[12] Press Reference Library (Southwest Edition): Notables of the Southwest (Los Angeles: The Los Angeles Examiner, 1912), 275.

[13] Langley’s City Directory of 1895, p. 903.

[14] Crocker-Langley City Directory of 1905, p. 1106.

[15] Crocker-Langley City Directory of 1912, p. 1012.

[16] San Francisco City Planning Commission Resolution No. 8039.

[17] S. F. Call, Feb. 18, 1910, p. 16, c. 4.

[18] S. F. Call, Jan. 27, 1910, p. 16, c. 4.

[19] S. F. Call, May 13, 1910, p. 18, c. 1.

[20] S. F. Call, May 14, 1910, p. 6, c. 4.

[21] Crocker-Langley Directory of 1910, p. 558.

[22] S. F. Call, Sept. 11, 1910, p. 35, c. 1.

[23] S. F. Call, June 12, 1910, p. 30, c. 5-6.

[24] S. F. Call, June 16, 1911, p. 11, c. 1.

[25] S. F. Call, Dec. 5, 1911, p. 11, c. 1.

[26] S. F. Call, Feb. 11, 1912, p. 32, c. 4-5.

[27] Ibid.

[28] S. F. Call, Feb. 24, 1912, p. 19, c. 2.

[29] S. F. Call, May 6, 1913, p. 18, c. 6.

[30] S. F. Call, July 2, 1913, p. 22, c. 1.

[31] S. F. Chronicle, Dec. 30, 1914, p. 9, c. 6.